Recent events in Greece have baffled many observers. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras walked out of talks with Greece’s creditors, calling a snap referendum on their proposals. It appeared to be crunch time. Tspiras denounced the EU’s ‘blackmail-ultimatum’, urging ‘the Hellenic people’ to defend their ‘sovereignty’ and ‘democracy’, while EU figures warned a ‘no’ vote would mean Greece leaving the Euro. Yet, even during the referendum campaign, while ostensibly pushing for a ‘no’ vote, Tsipras offered to accept the EU’s terms with but a few minor tweaks. And no sooner had the Greek people apparently rejected EU-enforced austerity than their government swiftly agreed to pursue harsher austerity measures than they had just rejected, merely in exchange for more negotiations on debt relief. This bizarre sequence of events can only be understood as a colossal political failure by Syriza. Elected in January to end austerity, they will now preside over more privatisation, welfare cuts and tax hikes.

How can we explain this failure? I argue three factors were key. First, the terrible ‘good Euro’ strategy pursued by Syriza, the weakness of which should have been apparent from the outset. The second factor, which shaped the first, is the overwhelmingly pro-EU sentiment among Greek citizens and elites, which created a strong barrier to ‘Grexit’ in the absence of political leadership towards independence. Third, the failure of the pro-Grexit left, including within Syriza, to win Syriza and the public over to a pro-Grexit position.

The ‘good Euro’ fantasy

The strategy pursued by Tspiras and his former finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, has been dubbed the ‘good Euro’ approach. Essentially, they argued that a resolution to Greece’s economic depression could be found within the confines of the single European currency. The failure of previous governments to do this was simplistically assigned to the fact that they ‘never negotiated’ with the Troika but merely implemented its demands. Instead, Syriza would make common cause with other anti-austerity groups and sympathetic governments across Europe, pushing for more favourable bailout terms. This involved an attempt to ‘delegitimise’ the creditors by appealing – as Tsipras did even when denouncing the creditors – to the ‘founding principles and values of Europe’, supposedly norms of social justice like ‘rights to work, equality and… dignity’. From this perspective, the referendum was never intended to be a decisive moment for the restoration of Greek democracy and autonomy. It was merely called to strengthen the Greek government’s position when bargaining with the creditors, which is why Tsipras never stopped seeking another ‘bailout’ even as campaigning was underway.

But to any clear-eyed observer, this strategy was disastrous from the outset, because it rested on two flawed premises.

The first was that the allies Syriza sought were either too weak, or simply did not exist. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the European response to the global financial crisis has been the near-total absence of any effective resistance to the conversion of a banking crisis into a fiscal crisis of the state and from there to the imposition of austerity. With the exception of Greece and Spain, elections across Europe have tended to shift goverments to the right, even – as in Britain – after five years of cuts to state spending. The lack of effective anti-austerity resistance itself reflects the wider collapse of left-wing political forces from the 1980s. The disarray of the rump parties of social democracy, clearly unable to offer any alternative to austerity, is merely the prolonged death rattle of this epochal defeat. This was never promising terrain for a ‘good Euro’ strategy.

One hope of Syriza was the rise of Podemos in Spain – like Syriza, a loose alliance emerging from street-level, anti-austerity protests. But, as Varoufakis rapidly realised, ‘there was nothing they could do – their voice could never penetrate the Eurogroup’. Similarly, while Syriza notionally classified EU governments as pro-austerity, anti-austerity and neutral, with pro-austerity governments ostensibly in the minority, it was unable to leverage any international support. The French – perhaps the main hope – promised support in private, but criticised Greece in public. Nor were the governments of other countries suffering from EU-imposed austerity sympathetic. In fact, Varoufakis recalls, ‘from the very beginning… [they] made it abundantly clear that they were the most energetic enemies of our government… their greatest nightmare was our success: were we to succeed in negotiating a better deal for Greece, that would of course obliterate them politically, they would have to answer to their own people why they didn’t negotiate like we were doing.’ It should therefore have been immediately clear to Syriza that the building materials for the progressive bloc it hoped to construct simply did not exist.

The second flawed premise was ‘leftist Europeanism’, the idea that the European Union is primarily about values of ‘social justice’, such that appeals to these values could overcome demands for austerity. Again, this notion was ludicrous from the outset. By the time Syriza was elected, the EU had already subjected the Greek people to grotesque abuses. These include: 25 percent unemployment (57 percent among youths) by 2012; the mass collapse of small businesses; a 25 percent rise in homelessness from 2009-11; a 75 percent rise in suicides from 2009-11; mass emigration; and a massive health crisis, with spikes in epidemic diseases and a drop in life expectancy of three years (a phenomenon generally only seen in war-torn countries), nonetheless followed by a further 94% cut in health funding from 2014-15. Even pro-EU liberals outside Greece are now reconsidering their naïve faith in ‘social Europe’ after what has happened there. To any Greek, the real values being pursued through the EU ought to have been crystal clear. As one Varoufakis advisor notes, ‘the only weapons… [Syriza brought] to the negotiating table were reason, logic and European solidarity. But apparently we live in a Europe where none of those things mean anything.’

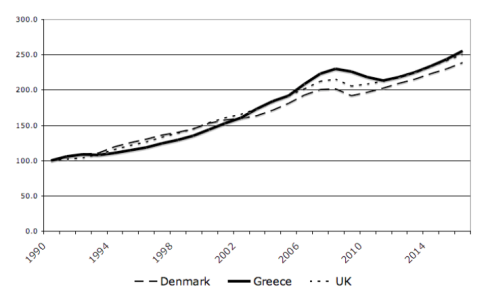

Eurobarometer: percentage of EU citizens expressing trust in EU institutions. Source.

Eurobarometer: what does the EU mean to you personally? Source.

As Varoufakis and Tspiras discovered almost immediately, EU institutions have little to do with democracy, either. The informal Eurogroup of Finance Ministers, Varoufakis notes, makes ‘decisions of almost life and death, and no member has to answer to anybody’. ‘From the very beginning’ (i.e. from their first meeting in February), Varoufakis encountered a ‘complete lack of any democratic scruples, on behalf of the supposed defenders of Europe’s democracy’. Germany’s finance minister told him: ‘Elections cannot change anything’. Some ministers agreed with Syriza’s critique of austerity, but essentially said, ‘we’re going to crunch you anyway.’ What further demonstration did Syriza need that EU leaders are not interested in social justice, only containing the Euro-crisis – and thereby protecting their own shoddy financial institutions from debt default and contagion – by making Greece the whipping boy of Europe?

The Greek fetish of European membership

Unsurprisingly, critics had declared the ‘good Euro’ strategy a failure as early as February, while Varoufakis’s post-resignation interviews reveal that its chief executors also swiftly recognised its flaws. So why did it ever appear a good idea in the first place? Ultimately, Syriza was elected on a platform both of ending austerity and remaining in the Euro – the latter position being shared by all of its main political rivals and by 80 percent of the public. This contradictory position reflects the attachment of Greek citizens and elites to ‘Europe’ as a refuge from their domestic political difficulties, and thus a reluctance to confront and resolve these difficulties alone.

As The Current Moment’s co-editor, Chris Bickerton, has shown, this is part of a general trend across the EU. From the 1970s, faced with crises of rising expectations and increasing social unrest, European elites have – through varying national trajectories – tried to create a new social, political and economic settlement by entrenching themselves within international elite networks. The EU’s structures are generally not supranational authorities but rather elite solidarity clubs, where ministers pursuing unpopular ‘reform’ agendas can draw upon each other’s support against their respective populations, thereby basing the content and legitimacy of their actions not on democratic mandates but on the legalistic European processes of policy coordination and harmonisation. By linking virtually every state apparatus across European borders, elites have thereby transformed once-sovereign nation-states into EU ‘member-states’, heavily constrained, with popular sovereignty deliberately negated. European elites can no longer imagine life outside of these structures, because it would represent a vast step-change: a need to re-engage with their own populations as the sole source of their authority, and the need to articulate clear political visions for their nations instead of relying on the latest EU action plan to guide their polities.

Each member-state has followed its own particular trajectory into this dismal arrangement. In Portugal, Spain and Greece, the process was strongly marked by their 1970s transition from authoritarian rule. In much the same way as the recent Scottish referendum proposed to make Scotland independent of the United Kingdom but immediately constrain its autonomy by retaining EU membership, these southern European nations emerged from authoritarian rule only to constrain democratic choice by swiftly joining the then European Economic Community. For the Greeks, joining ‘Europe’ was apparently a way to help draw a line under the past. It signalled their rejection of military rule, their ‘identity’ ‘as Europeans’, their distinction from authoritarian neighbours like Albania and Turkey. And it precluded the return of authoritarianism by locking Greece into various intergovernmental agreements and processes that entrenched liberal rights. The same motive and process had guided the formation of the European Convention on Human Rights in the early post-war years, and the later flight of Eastern European states from ‘Brezhnev to Brussels’, as Bickerton puts it.

Thus, for wide swathes of the Greek public, and especially the liberal and left elite, membership of the EU is valued precisely for its constraints. The fear, as Varoufakis himself clearly articulated, is that the beneficiaries of Grexit would not be the ‘progressive left, that will rise Phoenix-like from the ashes of Europe’s public institutions’, but rather ‘the Golden Dawn Nazis, the assorted neofascists, the xenophobes and the spivs’. His successor, Euclid Tsakalotos, issued similar warnings from the foreign ministry. Their fear was essentially of what the Greek people would do, left to their own devices.

This concern is hardly unique to Syriza. Across Europe, the dominant – perhaps only – elite justification for European integration is that its only alternative is a return to nationalism (or worse) and war. The Greek version of this politics of fear is simply mediated through the recent historical experience of military rule. Syriza’s embrace of this pessimistic narrative clearly signified a profound lack of faith in its own capacity to lead Greeks towards a more progressive future as an independent nation.

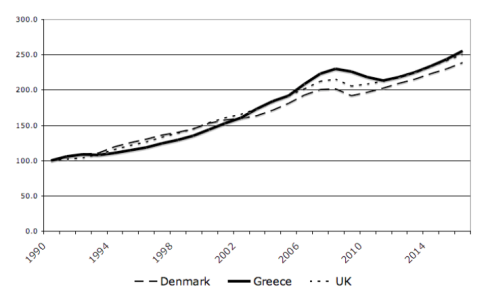

This quite widespread ideological attachment to Europe was undoubtedly reinforced by the apparent economic benefits of EU membership before the Euro crisis. In 1974, when the Colonels’ regime fell, Greek GDP per capita was just $2,839. When Greece joined the EEC in 1981, it was $5,400. By 2001, when Greece joined the Euro, per capita income had more than doubled to $12,418. Under the Euro, average incomes then nearly tripled to $31,701 by 2008. Greece literally appeared to go from third world to first in the space of two generations. In real terms, of course, the increase was always smaller – from $12,829 to $24,148 from 1974-2008 – but this was still a significant ‘catching up’ with other European states. As is now widely recognised, much of the post-2001 boom was fuelled by reckless borrowing and its benefits were always maldistributed, with a narrow oligarchy dominating a state-led patronage system. This is undoubtedly why the Greek oligarchy, while evading the consequences of austerity itself, has waged a strong pro-EU campaign, including through the media organisations it dominates, and is implacably opposed to Syriza, which had pledged to ‘destroy’ the ‘oligarchy system’. However, economic benefits also flowed to a wider coalition, with handouts like early pensions for professional groups and public sector unions supportive of the status quo.

Greek GDP Per Capita, current US$. Source.

Greek GDP Per Capita (Purchasing Power Parity) 1990=100. Source.

Combined, these factors seem to have made many Greeks leery of Grexit, even as the economy shrivelled. For some, when the crisis struck, there was apparently a guilty sense of the chickens coming home to roost – that ‘the party was over’ – with two-thirds of Greeks actually supporting austerity in 2010. Although this support collapsed over the next four years, fuelling the rise of Syriza, fear of the unknown remained very strong. Even in the most favourable scenarios, restoring the drachma would be hugely destabilising in the short to medium term and risk undoing the residual benefits of Euro membership. This motivation seems particularly strong among those with most to lose.

All of this helps explain the structural constraints facing Syriza leaders upon their election. The Greeks were both tired of austerity and yet fearful of exiting the Euro. Consequently, they demanded an end to austerity within the Euro. Squaring this circle was an impossible task.

But this should not let Syriza off the hook. Insofar as Syriza leaders understood that these popular demands were incompatible, they ought to have exercised political leadership by trying to lead the Greek citizenry towards a more rational position. The most crucial step was to outline a compelling vision for a Greek economy independent of the Euro, where life might be tough for a few years (but probably no tougher than under perpetual EU-imposed austerity), and recovery was eventually possible via the currency devaluation that every sane economist argues is both essential for Greece’s recovery and impossible within the Euro. This Syriza comprehensively failed to do.

Despite their leftist élan, its leaders seem just as incapable as their European counterparts of imagining a future for themselves and their country outside the strictures of European integration. Syriza’s failure remains one of leadership and strategy, irreducible simply to popular attitudes. The Syriza leadership has now embraced a deal that it openly admits is rotten, claiming ‘there is no alternative’. This merely signals a refusal to accept political responsibility for articulating an alternative. Ultimately, they – like the leaders of Europe’s other ‘member-states’ – are too afraid of the consequences of genuinely restoring autonomous, democratic decision-making to their nation. As Stathis Kouvelakis comments, this reflects their ‘entrapment in the ideology of left-Europeanism’. When Greek officials denounce the ‘almost neo-fascist euro dictatorship’, they are heaping the blame entirely on German sadomonetarism while evading their own failure to rebel against it, however difficult that rebellion would undoubtedly be.

As a consequence of this hesitancy, Syriza leaders spurned the growing social basis for a pro-Grexit line, which emerged despite, not because of, them. While in January 2015, 80 percent of Greeks favoured remaining in the Euro, by the time of the referendum this figure had fallen to 45 percent, with 42 percent favouring the serious consideration of Grexit.

The left’s failure to produce Grexit

This leaves one remaining question: why were those on the left, able to see all of the foregoing problems, unable to change Syriza’s course? After all, much of the above criticism of the ‘good Euro’ strategy was initially articulated by figures within Syriza, most notably Costas Lapavitsas, Stathis Kouvelakis and others members of its ‘Left Platform’. The Greek far left has also long demanded Grexit. Left Platform figures had adopted a position of ‘no more sacrifices for the Euro’ in 2012/13 and have long argued for default and Grexit, with apparently growing support. 44 percent of Syriza’s Central Committee backed the Left Platform’s call to break from negotiations and pursue a radical ‘plan B’ in late May. Tsipras was reportedly being constrained by their resistance in parliament in June. After the referendum, the Left apparently won over a (bare) majority of Syriza’s Central Committee to oppose capitulation, backed by many grassroots activists. Yet, only 38 Syriza legislators (out of 149) rebelled against the government (six of whom merely abstained). Although this left

Tsipras dependent on opposition legislators to survive, in subsequent votes that number has shrunk to 36 (with Varoufakis among the defectors), while Left Platform ministers have been sacked or resigned. Amazingly, the ‘good Euro’ strategy persists.

Part of the explanation for this is the nature of Syriza itself as a loose coalition rather than a traditional leftist party. Initially merely an electoral coalition, formed to contest the 2004 elections, Syriza became a party only in 2012, merging 13 political groups ranging from social democrats to hard-line Marxists. Syriza’s dominant parliamentary faction has always been Synaspismós, itself a democratic socialist coalition, led by Tsipras. Syriza’s ‘Left Platform’ – comprising the ‘Left Current’ and ‘Red Network’ – are relative newcomers and, even when joined by the Communist Organisation of Greece (KOE), also a Syriza member – simply lack the numbers required to impose their preferences.

Moreover, despite the 2012 merger, Syriza did not develop party structures capable of discussing, determining and imposing a collective ‘party line’. This looseness permitted a high degree of open internal dissent and had a ‘horizontalist’ flavour much celebrated by contemporary critics of traditional leftist parties. But the downside is that this organisational form effectively permitted the central leadership to determine policy, while more critical elements simply became a sort of internal ‘loyal opposition’.

Syriza’s leftist elements were not unaware of this, but were compelled to join the party having failed in their initial quest to form a broad, anti-EU alliance with the anti-capitalist left. As Kouvelathis describes it, the Left Platform crowd joined Syriza in 2012 only after these proposals left were rejected by the main component of Antarsya (Anticapitalist Left Cooperation for the Overthrow), a far-left coalition formed in 2009. The KKE, the Communist Party of Greece, also remained aloof. The sticking point was apparently the ultra-leftists’ insistence on a programme of immediate rupture from the Eurozone as the bulwark of ‘neoliberalism’. However, as noted earlier, in 2011/12 this position had virtually no popular support. Nor, reflecting the long-standing decline of Greece’s far left, did these far-left parties have any electoral standing.

Essentially, while Syriza had the wrong line but at least the capacity to get elected, the radical left arguably had the correct political line but lacked any capacity to translate it into policy. Following a crisis common to all European states in the 1980s, the Greek far-left has been extremely fragmented, remaining, despite the formation of horizontalist alliances, unable ‘to actually articulate an alternative project’, and producing ‘catastrophic electoral results’, according to Antarsya’s Panagiotis Sotiris. This strategic ineptitude led them, unlike Syriza, to fail to translate their mobilisation of Greeks in the 2011 ‘movement of the squares’ into party organisation and electoral success. This was arguably a serious failure of the horizontalist model with its renunciation of forming parties capable of seizing the state. As Sotiris laments: ‘we never realized that the question was about power… reclaiming governmental power. At that point, we did not have this position, but Syriza had it’.

Unsurprisingly, then, the Left Platform group threw in its lot with Syriza. But in so doing, it inevitably became somewhat marginalised and constrained: outnumbered within Syriza by centre-leftists and balanced within government by Syriza’s coalition partners, the right-wing Independent Greeks (ANEL). Through this Caesarist balancing act, as Kouvelakis recounts, ‘the government, the leadership, became totally autonomous of the party’. The lack of democratic structures within the loosely constituted party has permitted Tsipras to dominate: the Central Committee has not convened for months. But nor, it seems, has the Left Platform been willing to precipitate a full-on confrontation. Even when voting against the post-referendum ‘bailout’, it carefully manipulated its vote to try to avoid removing Tsipras’s majority support from within his party, the loss of which has traditionally triggered elections in Greece. (Ultimately, so many non-Left Platform Syriza MPs rebelled that this majority was lost anyway, although no election has been called.)

But these questionable tactics, an inevitable part of the difficulties of party politics, are probably secondary to the larger strategic failure, which was to neglect to present the citizenry with an alternative plan for Greece’s future outside the Euro until early July. Kouvelakis now admits this was a serious mistake.

It is not that the plan took forever to draft: it was already in hand long ago, but there was ‘internal hesitation about the appropriate moment to release it.’ This apparently stemmed partly from fears that Greece was ‘ready’ for Grexit. Lapavitsas has long argued for a managed and ‘orderly’ Grexit, but as late as 10 July he openly doubted whether any preparations had been made. Varoufakis’s subsequent revelation that only five officials had been tasked with this suggests that he was correct (as well as signifying his utter disinterest in alternatives to striking deals with the creditors). Essentially, reflecting its marginal position in the ruling coalition, the Left Platform was dependent on the governing part of Syriza to lay the technical ground for their Grexit strategy, which they clearly had no interest in doing. Its members had also become swept up in day-to-day events, Kouvelakis recalls, being ‘neutralized and overtaken by the endless sequence of negotiations and dramatic moments and so on… it was only when it was already too late… that [our] proposal was finally made public… This is clearly something we should have done before.’ The Left Platform thus failed to provide the leadership that their Syriza colleagues refused to provide and that their compatriots so badly needed.

Conclusion

What lessons can we draw from this sorry tale?

The main one is that the European left must shed its illusions about European solidarity. First, the EU is not, and has never been, a font of democracy and social justice. The left, broadly defeated at home through the 1980s, has increasingly put its faith in supranational institutions to protect human rights and social protections, including the EU’s ‘social chapter’. That this only ever expressed the left’s domestic weakness was starkly revealed when European elites combined after 2008 to inflict austerity on their own peoples, and domestic resistance was utterly ineffective. Appealing to EU leaders to uphold norms of democracy and social justice, as Syriza did, is clearly futile. Syriza should be credited with one achievement. It has finally pulled away the veil, forcing everyone to recognise the EU’s true character.

But, secondly, it is equally illusory to put one’s faith in European parties, peoples and social movements, in the hope of a transnational alliance capable of generating more progressive outcomes. This hope for a ‘counter-hegemonic bloc’, long expressed by Gramscian scholars of the EU, has been peddled for 20 years without success, expressed in forms like the European Social Forum, which ultimately go nowhere. Sadly, Syriza found little to no effective support beyond their own borders. Again, this reflects the collapse of progressive political organisations capable of turning humanitarian sympathy into meaningful political action.

This experience strongly suggests that the prevailing European order cannot be effectively contested by progressive forces at the European level. They are simply too weak and isolated. After all, part of the elites’ purpose in rescaling governance to the European level is precisely to outmanoeuvre opposition, which is rightly assumed to be less able to organise regionally than nationally. This suggests that progressive forces must operate primarily on the more hospitable terrain of the nation-state. They need to lead a movement among their own people, even if it means arguing with them, rather than relying on those abroad who already agree with them. This implies a need to recover space for this activism by reasserting the autonomy of domestic politics from European regulation – i.e., by reclaiming popular sovereignty.

Despite growing left-wing Euroscepticism, this step seems to remain anathema to most. Syriza’s leadership were openly leery of popular sovereignty, warning of a fascist revival. This fear is widespread among European elites, suggesting a strong suspicion of the masses, perhaps especially among supposed progressives. But even Syriza’s Left Platform seemed wary of articulating the necessary steps for the restoration of Greek autonomy, despite their clear premonitions of disaster. This is a sign of how deeply the ‘member-state’ mode of politics has been entrenched over several decades. It will be a hard habit to kick.

Another lesson concerns the organisational form and content of anti-EU resistance. Broad coalitions, rooted in societal mobilisations, are crucial, but insufficient without strong party organisation. Syriza’s formation as a party helped create the structures and programme necessary to help turn popular mobilisation into political power. It thereby achieved what every fashionable, ‘rhizomatic, horizontalist network’ – from Occupy to the Greek far left – has failed to: to exert some grip over state power and thus potentially leverage over social change. Yet, its absence of strong internal democracy also allowed its leaders to pursue an unworkable strategy and even betray the expressed wishes of the electorate. Against the Eurocrats for whom ‘elections cannot change anything’, the task is to rebuild truly democratic parties capable of articulating an alternative and attractive vision for the future of European societies.

Lee Jones

Tags: austerity, debt, democracy, Euro, Eurozone crisis, financial crisis, Germany, greece, Inequality, poverty, Tsipras, unemployment