Ever high minded, The New Republic has seen reason to explain to us why the Occupy movement is hysterical and dangerous. Worse yet, trotting out an Cold War trope, TNR thinks the General Assembly political form “has an air of group-think about it that is, or should be, troubling to liberals.” Group-think so very unlike, of course, corporate boardrooms, trading floors, and, dare we say it, editorial boards. (We struggle to remember the last war TNR failed, so predictably, to support.) Luckily, we have that venerable mouthpiece of radical criticism, Business Insider, to remind us of some of the reasons why one might be on the street these days. Its summary of the economic situation is excellent, and very helpfully arranged with illuminating graphics.

For our part, we think the Occupy movement, like most protest movements, is mixed, and still in formation. Having spent the weekend at Occupy Boston, and yesterday facilitating an open air class at the camp, perhaps the most noticeable and exciting feature of the movement is the desire and willingness to think everything anew. The freeing of the imagination may, in fact, be the first and most significant effect of these protests. And just about everybody there seems to be open to debating all kinds of new ideas.

Of course, the imagination can go anywhere, and the Occupy movement will have to make some choices down the road. To the end of trying to think through the different possibilities, we discussed alternative ways of thinking about debt and corporations at the class yesterday. Below are some of our initial thoughts on corporations. The basic message we were trying to work through was ‘democratize, don’t destroy.’

Our economy is based on artifacts. Property, contract, money, corporations, these are all economic domains based on law and convention. Markets themselves are not natural, they are products of law. There is no such thing as ‘the market,’ with necessary and natural features. There are markets. The ‘fictitious’ character of our economy sometimes becomes the object of attack, especially when some of these fictions seem out of control and not work to our benefit. Anyone who has been to an Occupy event will have met Ron Paulites, who not only want to end the Fed, but also return to the gold standard. The return to the gold standard is offered with the, in our mind misguided, comfort of appearing to return to something concrete – gold. Abolish the fiction, so we can get back to the real thing. (A return to the gold standard would contract the money supply so severely that it would make the credit crunch of 2008 look like a hiccup.)

But it’s not just the Paulites who want to abolish the economic fictions that seem out of control. One also sees a lot of signs against corporations. ‘Corporations are not persons,’ is a familiar one. In so far as these signs are protestations against the Citizens United ruling, which used the fact that corporations are ‘legal persons’ to argue that they have free speech rights, we agree with these signs. But these signs often express a kind of parallel antagonism to the Paulite rejection of fiat money – abolish the fiction, return us to the real thing. Real persons, actual gold.

That is, in its roughest outlines, the ‘destroy’ side, or at least ‘refuse’. But the problem is that in large, global economy, based on the division of labor, there is no way out of such abstract or seemingly ‘fictitious’ relationships. And in fact, there are some very good things about them, on the basis of which one could start thinking about alternatives. In the case of corporations, we can think of at least three aspects of its legal or ‘fictitious’ personality that are a good thing. For one, abstracting for the moment from the specific rules of ownership and control, a corporation is a large amount of cooperative workers who work towards a common end. It is a collective economic agent. As such, it can take advantage of economies of scale, and these economies are potentially enormous (think of electricity, or steel, or even health insurance. Those actuarial risks are much more reliably calculated over a massive population than a small one.) There is no reason, in principle, why these economies of scale cannot benefit everyone. One can imagine large scale production dramatically reducing the amount of hours any given person must spend doing necessary work. That’s not our society – in which one in six have too little or no work, while many of the rest have to work too long. But it could be our society – and an important feature of that society would be using the productivity of large scale enterprises to meet human needs with minimal effort.

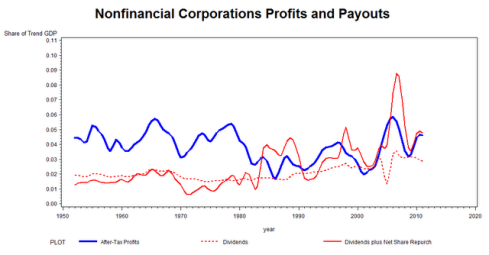

Second, a corporation is a separation of ownership and control. The ‘mom and pop store’ – the real fictions of the American economy, since 80% of US workers are employed in businesses of 500 or more (more than any other industrial economy) – is one where ownership and control lie in the same persons. But a corporation works by this separation owners and controllers, shareholders and managers, which is part of the reason why this construction ‘legal person’ is required. Over the past thirty years the ‘shareholder revolution’ has meant that this separation of ownership and control has worked largely against public interests. Previously passive shareholders have demanded higher profits, bigger dividends, which required transforming managers into creators of (short-term) shareholder value rather than managers of a long-term enterprise with various interests (worker, public, etc…) at stake. There is not much to defend in the old, pre-1980s managerial capitalism, but what the new relationship has meant is distributing more value to shareholders by squeezing workers. Slackwire recently graphed dividends against corporate profits, and produced a great graph of the shareholder revolution, showing the rapid rise in dividends plus net share repurchases (read the whole post, it’s excellent):

These dividend payouts, and shareholders cashing in, came from reorienting activities to the short-term share values, and by keeping wages low – hardly an arrangement that has served the public interest. (Especially since households compensated for stagnating wages by borrowing, and we know how that has gone.) But there is nothing necessary about this particular relationship between owners and controlers.

In fact, the separation of ownership and control at least used to be considered, by the Left, as one of the good things about corporations. It suggested that, against reigning ideology, the rentiers (shareholders) didn’t do much, since it was managers that ran day-to-day operations. Why, then, not euthanize the shareholders, have workers hire managers, and democratize the firm? And more broadly, the point is that the relevant stakeholders in a corporation – whose very existence is recognized, in American law, as necessary only to serve a public interest – are not just shareholders but also its workers, and the general public. As an artifact of law, the structure of ownership and control could be changed so that the idea – creating this collective agents for the public good – could better fit reality. (The best summary we’ve read on these questions is still the ‘Governance’ chapter of Doug Henwood’s Wall Street, available for free download.) Again, this democratization of the corporation hinges on seeing its artificiality or ‘fictitiousness’ as a good thing – as a feature of it being a creature of law, which we can change and control.

Finally, our one other thought is that corporations are said to take risks, and to engage in risky behavior that endanger the wider community. And part of the reason why it does that is because of its fictitious personality, the fact that its managers and shareholders only bear limited risks, that corporations can ignore all kinds of negative externalities, and this leads to bad outcomes. This may be true, but it is not an inherent feature of collective economic agents. It’s a matter of how we have constructed laws and incentives, such that we often socialize the risks but privatize the benefits of corporate activity. But there is nothing in itself wrong with giving certain collective agents the power, within appropriate constraints, to take risks. Taking risks, making a bet on the future, is a necessary feature of large scale economic activity and progress. It would be nearly impossible for an economy to do things like develop new planes, which take decades to develop, test, and manufacture, or new energy technologies, if it did not allow groups to take a bet on the future, to take risks with some portion of our economic surplus. How we arrange which risks are taken, and who bears the relevant risks, as well as who benefits from the distributions is again a matter of law. But it is not the risk-taking itself that is the bad thing about corporations.

These are not final positions, but initial thoughts, produced in response to the emerging economic thinking of the new Occupy movements, and with the hope that the initial, quite justifiable, feeling of rejection of fictions might be transformed into a more positive and constructive attitude, that finds a vision of the future in the seedbed of the present. The other alternatives we have heard discussed, especially ones that try to eliminate all of our seemingly fictitious or unreal economic practices, seem to us to be more of a rejection of the division of labor and large scale production itself. It’s hard to find a positive vision in that.

Two comments: The New Republic is not of one mind on OWS. The editors took the position you rightly deplore, but senior writers Cohn, Judis, and Noah are of a different opinion:

http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/96111/occupy-wall-street-grassroots-political-action

http://www.tnr.com/blog/timothy-noah/96216/about-those-protests

Second, it would indeed be a fine thing if corporations always acted in the public interest, and all other social actors as well. But one needs to be wary about assuming that simply broadening control to “stakeholders” such as employees and the general public, to use your two examples, will have only benign effects. Indeed, stakeholder influence in Germany, where Mitbestimmung made unions privy to corporate strategy and books, has not had only benign consequences. It contributed to the development of a dual labor market, in which insiders protected their jobs and relatively high wages and benefits at the expense of outsiders, who might have benefited from a different representation of interests in the boardroom–if, indeed, the boardroom is the appropriate place to expect the whole of a society’s diversity to find representation. The general interest is a beautiful but elusive thing, and any particular set of institutional arrangements will tend to promote a different notion of what the general interest is. Rousseau, who embraced a mystical idea of the way in which the general interest emerges from the silent communion of individual wills, probably did the world a disservice by coining a phrase that implies the existence of a unique and uncontentious generality. A case in point: the currently fashionable consensus in Europe is that if the banks must be saved by the citizenry, then citizens should be represented on the boards of banks as voting shareholders. But banks have been nationalized before, and “citizen” representation via government seats on bank boards did not prevent improvident, foolish lending or a multitude of other sins: see the Crédit Lyonnais scandal for starters.

It’s not just the Ron Paul fans that like gold, http://www.thegoldstandardnow.org/

I noticed the TNR article defended Capitalism. Capitalism, like Communism (and all -isms), is a religion. It bears the same relationship to free enterprise that pragmatism bears to practicality – it sets up a dichotomy that in the end is irrational – reflecting the fact that in the real world there are no dichotomies. This TNR crontributor (like Obama), having drunk the Capitalist kool-aid, is somewhere to the right of Richard Nixon, not really a liberal. Nonsense words like “Capitalism”, since they introduce confusion, serve as a propaganda tool for those wishing to project power or marginalize others.

This article supports the concept promulgated by the Sustainability Movement that corporations must not only consider profit but also people (employees and the public) and the planet. Adoption of this “triple bottom line” will best result in maintaining the advantages offered by the author without the currently experienced horrendous negatives. Sustainablility advocates need to support OWS and OWS should realize how much in common they have with sustainability advocates. By doing so we can realize the advantages of corporations without destroying our culture or our planetary support system.

I believe that corporations that buy major purchases should become incorporated. Think of it this way resources belong to the people, so if billion dollar companies are buy say allot merchandise say to rent for example , that company should be force to be incorporated so others can buy shares : A “Incorporated Resource Law” if you may. A bill should be created , so that these billion dollar company’s should at least give 25 percent of there shares to be bought.

Mark I like that prospect if the government would pass such a bill, resources are all of ours, that’s true. these billion dollar companies should also be forced to donate 10 % of there earning on public good too.