One of the defining moments of the EU referendum campaign was Michael Gove’s remark – directed at all the professional economists predicting a Brexit vote would produce economic disaster – that “people in this country have had enough of experts”. This is now seen to have initiated a terrible era of “post-truth” politics. For the experts themselves – many of them, my fellow academics – this is deeply disturbing, signalling the inexorable rise of irrational, fact-free political debate. But what people have had enough of is not experts or expertise, per se; rather, it is the automatic, assumed authority that experts wield over non-experts.

The rise of “experts” to positions of authority in public life is intimately connected with the decline in popular political participation over the last few decades. Society has always needed technical experts to provide advice and implement policies, but increasingly “experts” have taken a central place in decision-making itself. A burgeoning array of issues have been removed from the domain of democratic contestation and handed over to unelected technical experts to decide. In many jurisdictions, legal changes have locked in this turn to “evidence-based policymaking”. The obvious example is the rise of independent central banks. Populated by professional economists, these now control monetary policy – once a matter of intense political contestation between forces favouring inflation control (typically, capital) and those favouring full employment at the expense of some inflation (typically, organised labour). More generally, the rise of quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations (“quangos”), judicialised bodies, and various commissions and inquiries since the 1980s marks the depoliticisation of many areas of public policy, and the growing authority of technocrats – people whose power derives not from their popular support but their technical expertise. These technocrats have also started coordinating their work across borders, forming transnational governance networks even more remote from popular democratic control. The European Union is only the most obvious example.

There has always been a strong class basis to this shift. Relocating decision-making from representative bodies to technocratic agencies reduces popular control over policymaking while endowing skilled professionals with unprecedented authority. As David Runciman recently argued, increasing evidence of political division between highly- and poorly-educated citizens reflects this divide, with the authority-wielding professions increasingly confined to an ever-narrowing social elite. The shared social background and values of technocrats and those they often seek to regulate – and the increasingly obvious “revolving door” between them – also helps bias governance outcomes in favour of the already wealthy and powerful, rather than serving the public interest. In short, there is nothing neutral about the political rise of experts, despite its frequent presentation as such. Part of the backlash against the attack on “experts” is this class seeking to defend its own power and authority. It also reflects a Remainer fantasy that if only the public were more educated, Remain would have won – as if more mind-numbing courses on the institutional structures on the European Union could somehow magically erase all of society’s social, political and economic contradictions and conflicts.

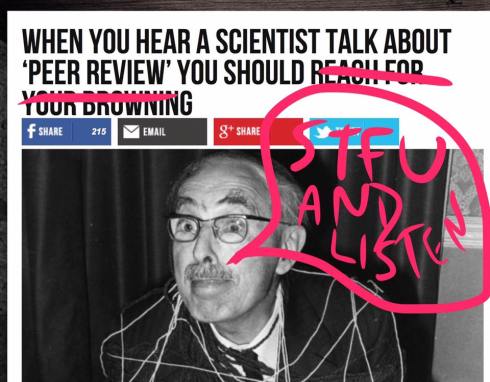

However, this reaction is overblown: it is not the case that ordinary people have lost all faith in experts, nor have they irrationally embraced “post-truth” politics. What they are revolting against is the automatic, assumed authority of experts. Due to the long decline of political contestation, many experts have become far too accustomed to being listened to with extreme deference; they expect their expertise to translate automatically into authority. It is this assumed authority that rankles with the non-expert: the presumption that, simply because someone has a PhD in a given area, no one else is permitted to voice an opinion. The expert does not even have to explain themselves: the mere invocation of their qualifications should apparently suffice to quell all dissent.

Examples of this abound, but one recent case is the widely-reported Twitter spat between UKIP funder Aaron Banks and historian Mary Beard over whether the Roman Empire was “destroyed by immigration”. Beard slapped him down: “you all need to do a bit more reading… Facts guys! … you guys don’t know Roman history… this might be a subject on which to listen to experts!” Banks defended his view, and was quickly vilified for trying to “mansplain” Rome to the noted female classicist. But his most notable comment was: “Where’s all your counter arguments & facts then?” Notably, Beard supplied none – she just dismissed him as ignorant and asserted her expertise. As the Huffington Post aptly summarised, his crime was failure to “defer to a respected historian’s perspective”.

But why should anyone defer to experts? There are many reasons to think they should not. Most obviously, experts are very often wrong – sometimes disastrously so. Winston Churchill’s “personal technocrat”, Dr Frederick Lindemann, advised the British government that the 1943 Bengal famine was due to overpopulation, counselling against sending relief. Six to seven million Bengalis starved to death. In the 1960s and 1970s, educational psychologist Sir Cyril Burt told the government that black children were genetically less intelligent than whites, holding back the shift to non-selective schooling. In the 1990s, government scientist Dr Robert Lacey warned that, by 1997, a third of the British population would have contracted Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease from eating beef contaminated with “mad cow disease”. The much-touted rise of “evidence-based policymaking” in the 1990s – reflecting the growing depoliticisation of public life – produced swathes of “quack policy”, justifying burgeoning state interference in private decision-making in the name of “public health” or “happiness”. Policies on passive smoking, alcohol pricing, sugar taxation and so on have all been adopted following scientist-backed campaigning – despite the fact that the evidence base is often extremely weak and the policies have often failed. As an IEA review comments, “evidence-based policymaking” has often been less about scientific rigour than a “mechanism for academic elites to impose their own values on society as a whole, showing contempt for the wishes of the public.”

This clearly extends to research around the EU referendum, where expert authorities have projected their value judgements as truth. The International Monetary Fund, the Treasury, and virtually every professional economist, made bleak predictions about the immediate economic impact of a Brexit vote, which have already been proven badly mistaken. Likewise, a study by Imran Awan of Birmingham City University and Irene Zempi of Nottingham Trent University, released by the charity Hope Not Hate, was found to have vastly exaggerated the positive reaction to the shooting of Labour MP Jo Cox during the referendum campaign. TCM has exposed similar exaggerations or distortions around Brexit by the Electoral Reform Society and #PostRefRacism, both of which had academic input. Other “research” is just openly spiteful, like the UEA academic who discovered a correlation between Leave voting and obesity (not-very-sub-text: Leave voters are stupid and fat).

Unsurprisingly, then, experts are not immune from value judgements that can powerfully shape their pronouncements. Moreover, even when they strive for objectivity, their knowledge is only ever partial. Especially in the humanities and social sciences, everything but the most basic facts is contested, because there are always many ways to interpret data. All real “experts” know this; indeed, many academics (especially those influenced by post-structuralism) have been preaching for decades that there is no such thing as objective truth – only a set of competing “truth-claims”. But many nonetheless splutter with outrage when a non-expert dares to challenge their particular truth-claim.

This is arguably the nub of the issue: the growing political inequality between the “experts” and the masses. Some clearly believe that experts do not even need to justify or explain their perspective to the less-educated; the gap between their credentials should short-circuit the need for any discussion. But in a democracy, citizens are equal. Credentials do not entitle one to a greater say or, as some now openly fantasise about, more heavily weighted votes; and nor should they. Ironically, many “experts” involved in educating students would agree that a good citizen needs to think critically, to not accept received wisdom unquestioningly, and to exercise discriminating judgement. A citizen who fails to do this is evading their responsibility, simply casting their vote on the say-so of authorities, rather than on the basis of their own reason. An expert who denies a fellow citizen the possibility of discussion and debate, and thus proper understanding of issues, therefore corrodes democracy itself.

What non-experts are rightly reasserting, then, after a long period of tightening technocracy, is their equality as political subjects. Experts still have a political role to play – but as citizens informing and participating in debate, not as automatic authorities to whom mere mortals should automatically defer.

Lee Jones

The Gove quote is a partial one (interrupted by interviewer)

he said (twice) – had enough of experts… the ones that got things consistently wrong…

sounds fair?

https://sites.google.com/site/mytranscriptbox/2016/20160603_sk

Gove “…..I think the people in this country have had enough of experts with organisations from acronyms saying –

Faisal Islam: This country have had enough of experts?! What do you mean by that?!

Michael Gove: “……From organisations with acronyms saying that they know what is best, and getting it consistently wrong –

Faisal Islam: The people of this country have had enough of experts?!

Michael Gove: Because these people, these people are the same ones who got consistently wrong what was happening –

Faisal Islam: This is proper Trump politics, isn’t it.

Michael Gove: No, this is actually a faith in the –

Faisal Islam: It’s Oxbridge Trump.

Michael Gove: [laughs]: It’s a faith, Faisal, in the British people to make the right decision –

Yes, it is a bit ironic that the widely quoted belief that Gove said ‘People have had enough of experts’ is itself a good example of ‘post-truth’ politics. He only appeared to say that because the interviewer kept interrupting him before he could finish his sentence.

But apart from that point, this is a good and thoughtful article: “expert authorities have projected their value judgements as truth”. Even simple points like “in a democracy, citizens are equal” are well worth re-iterating.

You need to change that grey text to black. It will be easier to read and your ideas will be better understood. PTxS