A year ago, following the EU referendum, many commentators were convinced that the Brexit vote had ushered in a generation of Tory hegemony, and the left would be permanently confined to the margins. Earlier this month, the Labour Party sharply improved its electoral performance with its most left-wing leader ever, and its most radical manifesto since 1983. Hailed by adoring Glastonbury crowds, Jeremy Corbyn himself has gone from zero to hero in a matter of weeks. Most of those commentators seem to have forgotten their earlier predictions in their haste to celebrate a Corbyn “victory”. But their gushing enthusiasm is no more measured than their earlier gloom.

A proper reckoning with the election result needs to start from the position that the EU referendum was never a hard-right victory in the first place. It then needs to be remembered that Corbyn still lost the election. Labour won only 262 seats, on 40% of the vote, to the Tories’ 317 seats, on 42.3%. Despite her manifest weaknesses, Theresa May won more votes than any prime minister since 1992. Corbyn’s “victory” amounts to averting catastrophe and making the Labour Party look like a serious contender for power again. A sober analysis of how this was achieved tells a less heroic story than the myth now developing around Corbyn.

A combination of different factors, with strong regional variation, helped the Labour Party electorally. Moreover, underlying Corbyn’s electoral success are elements of a political approach from Labour that is depressingly familiar and unattractive.

How Corbyn survived

Crucially, the Conservatives ran a totally dismal campaign. Theresa May was exposed as a robotic technocrat, shrill and inconsistent. She failed to persuade anyone but Tory and former UKIP voters that the election was solely about Brexit and her leadership, allowing Corbyn to reframe the election as being about socio-economic issues, where the Tories are weak.

Conversely, Corbyn had an excellent campaign from the outset – partly, it seems, by accident. In retrospect he appears to have ridden a tidal wave of support, but this is rather misleading. Whereas the Tories took the fight into apparently vulnerable Labour seats, Corbyn waged a defensive campaign in the Labour heartlands. Many rightly speculated that his remarkably large rallies in such areas were largely intended to shore up his position in the face of an apparently inevitably post-election leadership challenge. Instead, these events, widely covered on TV and social media, seemed to inspire people that something different was in the air. The “ground war” had a similar defensive quality, with Labour HQ instructing activists to shore up incumbents, rather than going on the attack. It was only as the polls shifted that grassroots campaigners, on their own initiative, shifted to proactive campaigning in neighbouring marginals.

Corbyn’s team was able to quickly assemble a remarkably popular manifesto. Despite two years of relentless infighting and plots, party wonks had somehow managed to find time to work up and cost specific policies. This was a real game-changer. Many had previously been frustrated with Corbyn’s apparent inability to translate fine-sounding words into concrete proposals; the sudden production of a costed manifesto gave him a serious edge over the visionless, warmed-over One Nation Toryism offered by Theresa May, in an uncosted manifesto that contained an electorally-deadly “dementia tax”. The Corbyn team’s leak of the draft manifesto was also a masterstroke. It confirmed the policies as widely popular, bouncing the party’s general executive into approving it.

The popularity of Labour’s policies was expressed in the remarkable cross-class support the party attained. This also reflects in part Corbyn’s appeal to the populist mood, where he had the advantage of being a lifelong outsider – a position burnished by attacks over his previous positions and associations. By comparison, Theresa May looked every inch the elite technocrat that she is.

Labour won a plurality of votes among all workers, with only retirees backing the Tories. Much has been written since the election suggesting that Labour under Corbyn has essentially become a middle-class party. Although Labour’s support has certainly become more middle-class over recent decades, there is no sign of any big shift under Corbyn specifically. If we look at how people in particular social grades voted, compared with 2015, Labour and the Tories both gained more support across all categories, but Labour still did a little better with less well-off voters. (NB this data measures occupational grade, not social class.)

|

AB |

C1 |

C2 |

DE |

| Labour |

35 (+9) |

41 (+12) |

39 (+11) |

46 (+12) |

| Conservative |

44 (+4) |

41 (+7) |

44 (+12) |

34 (+9) |

Table 1: Proportion of voters within each social grade won by Labour and the Conservatives respectively

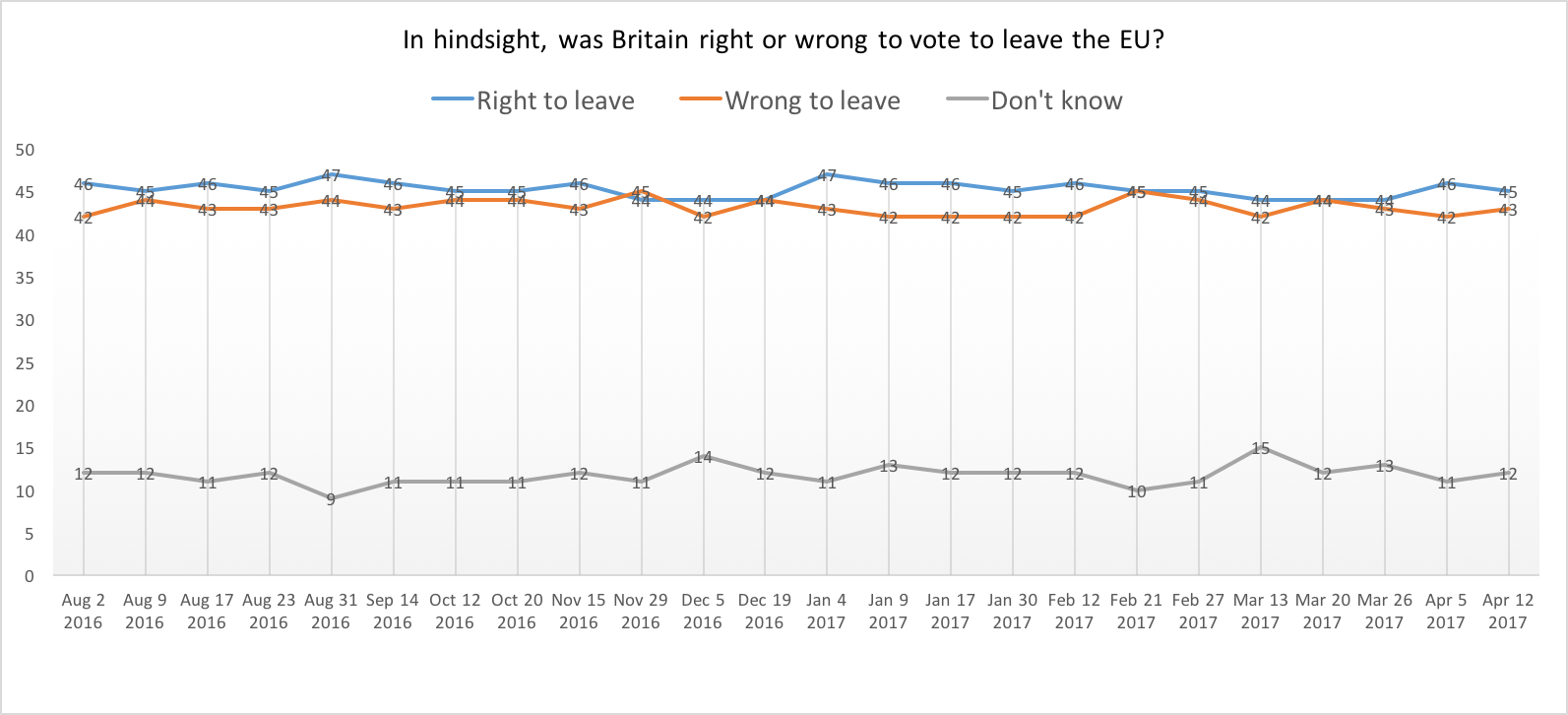

Nonetheless, what’s striking is obviously the rather weak association between class and voting behaviour – especially when compared to age. Corbyn managed to boost substantially the Labour vote among under-45s – not merely among the very young (see Fig. 1). Early boasts from the NUS president of a record 72% turnout among 18-24s turned out to be self-congratulatory and baseless nonsense, but turnout did return to early-1990s levels (see Fig. 2). This is crucial insofar as there is now a yawning generational gap in voting patterns (see Fig. 3). After a decade of disengagement under New Labour, the EU referendum seems to have kick-started politics again for the youngest generation.

Fig. 1: Turnout by age group

Fig. 1: Turnout by age group

Fig. 2: Conservative-Labour gap by age

Fig. 2: Conservative-Labour gap by age

Also crucial was Labour’s stance on Brexit, where a triangulating fudge actually became an electoral asset. In pro-Leave constituencies, Corbyn’s insistence on respecting the EU referendum result was decisive. As Paul Mason, who campaigned in several pro-Leave areas, reports, this was needed merely to gain a hearing for Labour on the doorstep. This helped to pull back 20-30% of UKIP’s vote for Labour and held off the Tory advance in the North and Wales. Had Labour run on an anti-Brexit ticket, the Tory capture of Mansfield would have been replicated far more widely.

In some pro-Remain constituencies, however, particularly in the metropolitan areas, Labour candidates expressly pledged to oppose Brexit. This arguably helped attract votes from hardline Remainers and, coupled with substantial tactical voting, explains the significant swing from the Greens and LibDems to Labour. This is why Labour was able to hold constituencies like Bermondsey.

Finally, the terrorist attacks during the election campaign probably had some effect. The Manchester bombing had surprisingly little impact at first. As the person who facilitated the movement of Libyan radicals back and forth to the UK, Theresa May has escaped with staggeringly little accountability. However, nor were the Tories able to smear Corbyn as “weak on security”. Instead, Labour adroitly made an issue of police cuts, while the Tories had little to offer but irrelevant and draconian measures like internet regulation. There was virtually no real discussion of the causes of Islamist terrorism (reversing police cuts won’t solve the problem either), but Labour came out of these horrific events with a reinforced case against austerity.

The left has not yet closed the void

The electoral advance for the Labour Party is significant, but at this stage it would be unwise to put too much hope in it for a revival of mass politics.

In the first place, despite its vastly increased membership thanks to Corbyn, the Labour Party itself is still poorly suited as a vehicle for a new popular movement. Surprisingly little has been written on the Labour “ground war” but it does not seem that the party sought to harness its expanded membership as foot soldiers, and even the pro-Corbyn Momentum faction seemed to play a surprisingly weak role. This reflects the Labour party’s attenuated internal democracy, which has made it resistant to, reluctant to engage with, and even suspicious of, the groundswell generated by Corbyn.

The party machinery, and its parliamentary wing, stayed remarkably disciplined during the campaign, particularly given the previous two years of backbiting. Thanks to the result, Corbyn’s enemies are now forced to smile to his face. But they are still in position. Most party hacks, unelected and elected alike, remain opposed to even the mild social democratic programme that Corbyn stands for. Many campaigned by distancing themselves from him, to save their own skins. Their loyalty is paper thin; they are not true believers but rank opportunists who still believe, in their heart of hearts, in centrist, Blairite policies. It remains to be seen whether Corbyn has the political authority and will to restructure and democratize the party, as he often declares he wants to. His previous treatment of Momentum – cutting them off at the knees after an onslaught from his treacherous deputy, Tom Watson – suggests a reluctance to take the tough decisions needed.

More important, the party and its base remain deeply divided, socially and politically, most importantly over Brexit. The long-term decline of the trade union movement has resulted in Labour’s support being more evenly split between its traditional, deprived, working-class heartlands and the relatively prosperous, liberal, metropolitan middle classes. Its disarray over Brexit expresses this divide. The election did not bridge the divide with a coherent new compromise; it did not even paper over the cracks, because different parliamentary candidates were campaigning on completely different platforms. If Labour was suddenly thrust into power it would struggle to offer anything more coherent than the Tories on the major task facing the country, and rifts would rapidly re-emerge.

A leading force in this division would be the leftists currently celebrating Corbynmania but who spent the last year sneering at Brexit voters as knuckle-dragging racists. They have not suddenly changed their minds about this. They prefer a fairytale version of the general election as some kind of heroic, progressive fight-back against dark forces that never actually existed. Their support for the EU, and their derision for voters, expresses the long-term retreat of the political class away from the people and into the state, and this is yet to be reversed. Corbyn’s ability to engage with the public is admirable, but it is not widely shared. Comparing the reaction to the Grenfell Tower disaster with that towards the Brexit vote, indicates that leftist elites prefer the poor when they appear as vulnerable clients of the welfare state, rather than bolshie political actors in their own right.

Finally, despite Corbyn’s dumping of Blairite fiscal policy, both Corbyn’s manifesto and his campaign drew on New Labour techniques and themes. The party’s balancing act on Brexit and immigration was a careful piece of political triangulation, characteristic of the Blair era. During the campaign, Corbyn was quick to respond to the massacres in Manchester and London by calling for more police on the streets, a classic Blairite move to exploit fear and institutionalise insecurity. Blair may have gone, but the Labour Party both in its approach to police security and its wider approach to social security remains very much a party focused on the politics of safety rather than the politics of self-government.

Lee Jones and Peter Ramsay